1902년, 조선인 하와이 이민선을 타다 (My Ancestors Who Boarded the SS Gaelic) - A Korean American Immigration History Series

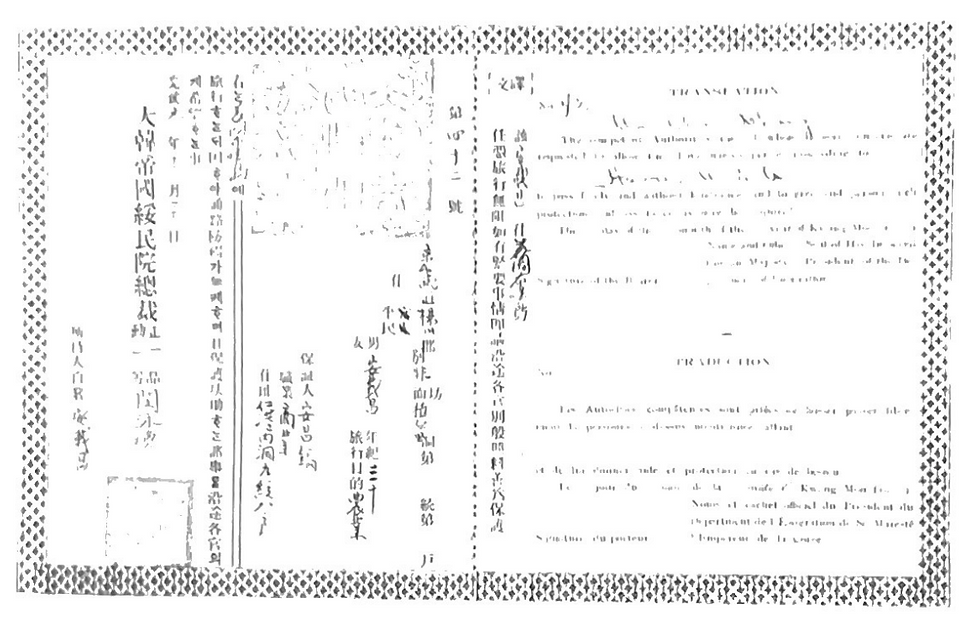

- Heaja Kim

- Aug 1, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 26, 2025

In this and next few issues of IKEN Quarterly, I will have the privilege of sharing the story of four of my ancestors who came to the United States in the early 20th century. Two boarded the SS Gaelic in 1902, and another one in 1903 on the third ship to bring Korean immigrants to Hawaii, with the last one arriving in Hawaii in 1926 in exile. Their migration represents the history of early Korean immigration to the United States and the contributions made to the Korean Independence Movement by Korean Americans. I am fortunate to have access to this family history, thanks to Hyung-ju Ahn, aka Uncle Henry, who meticulously researched, documented, and chronicled it in 1902년, 조선인 하와이 이민선을 타다 (2013, 푸른 역사), roughly translated as 1902, Joseon People Board the Immigration Ship for Hawaii.

According to Uncle Henry, the Ahn family’s history can be traced back to the Koryo dynasty when a clan member passed a civil service examination, which must have made the family relevant enough to leave a record that could be traced. Their fortunes improved dramatically when three successive generations of the Ahns passed the civil service examinations starting in the reign of King Sejong the Great of the Joseon dynasty. By the 1600s, the Ahn clan was able to achieve the distinction of becoming one of the most powerful and elite families through marriages to the extended families of King Seonjo and King Injo.

However, their rise in social rank and the attendant prosperity resulted in a reversal of fortune in which they were charged with treason when the family became embroiled in the palace faction intrigue involving Jang Hui-bin, aka Lady Jang. Consequently, the Ahn clan was ruined financially, socially, and reputationally, and was forced to hide out in a small village northeast of Seoul with no prospects until they got their social status restored during the reign of King Jeongjo the Great. However, they were able to achieve only a modest success which left many of their descendants struggling financially with no inherited land.

My great grandfather Chang-ho Ahn was even worse off than the rest of the Ahn clan because he lost his father when he was just 10 years old and had to work in the fields to support his mother and two younger sisters. Fortunately, however, his paternal aunt, who was a beloved daughter-in-law of a prosperous family, extended financial help and educated him alongside her own son. When he was 17, in 1901, Chang-ho made such a favorable impression on Byeong-hyeon Choi, a businessman and an elder at Naeri Church, the first Methodist church in Korea, founded by Henry Appenzeller and located in Inchon, that Chang-ho became his son-in-law.

Around the turn of the 19th century, the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association began to look to Korea for labor to meet the increased production of sugar cane after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed and the Japanese laborers began to leave Hawaii for the U.S. mainland for better wages. The Association found the right person in Horace Allen who had the ear of King Gojong because Allen successfully treated the injury sustained by Queen Min’s nephew during the ill-fated Gapsin coup (갑신정변), one of whose leaders was Philip Jaisohn (서재필). A severe famine caused by repeated drought and flooding between 1898 and 1901 presented Allen an opportune moment to persuade King Gojong to send Korean workers to Hawaii starting in 1902.

To facilitate the recruitment of Korean workers to work in Hawaii, the Deshler East-West Development Company was established, and the Company secured the help of the Reverend George Heber Jones, who was the head pastor at Naeri Church. Chang-ho’s father-in-law was one of the two congregants put in charge of recruiting immigrant workers. Because Koreans were not sea-faring people and prioritized their filial duty above all else, leaving their family and ancestral land was a hard-sell for most Koreans. Eventually, though, they were able to recruit 120 people by overstating the wages the workers would earn and the likelihood of establishing their own church in Hawaii.

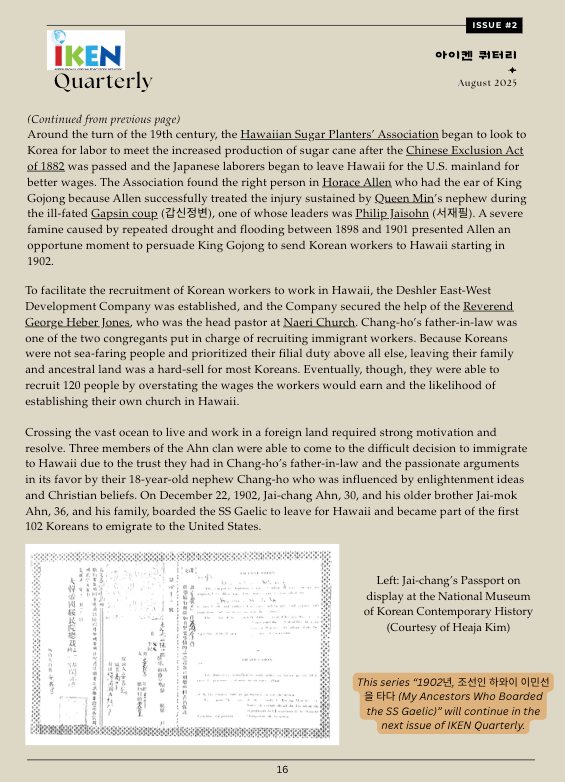

Crossing the vast ocean to live and work in a foreign land required strong motivation and resolve. Three members of the Ahn clan were able to come to the difficult decision to immigrate to Hawaii due to the trust they had in Chang-ho’s father-in-law and the passionate arguments in its favor by their 18-year-old nephew Chang-ho who was influenced by enlightenment ideas and Christian beliefs. On December 22, 1902, Jai-chang Ahn, 30, and his older brother Jai-mok Ahn, 36, and his family, left Incheon and became part of the first 102 Koreans to emigrate to the United States.

Comments